Reading the Dirt

Most archaeologists loved digging in the dirt as a kid. Some wandered their grandparents’ farm, imagining life hundreds of years ago, or went rock-hunting on family road trips out west. For these sandbox pioneers, a fascination with reading the dirt evolved into the art and science of archaeology. Archaeologists seek to build a better picture of the past as well as a better understanding of the troubled history of their own field—all of which contributes to bettering our shared present and future.

Great Prospects

Luther has long provided excellent training in archaeology. Since the 1960s, our anthropology program has offered archaeological field school, where students get hands-on experience finding sites, excavating, recovering artifacts, recording information, and processing materials—a rarity at the undergraduate level and particularly in Iowa.

Marit Bovee ’04 has spent most of her career at the federal level, working to balance the needs of development with the preservation of cultural resources.

Since the summer of 2000, the field school has been run by professor of anthropology Colin Betts ’93. Betts’s school was an invaluable start for many current Luther-trained archaeologists, including Marit Bovee ’04. “I’m at the point in my career now where I look at resumes and make recommendations on whether to hire folks or not, and field school is an absolute requirement,” she says.

Bovee and others are seeing growth in their field and insufficient qualified college graduates trained to do archaeological work. In the next decade, the need for cultural resource management workers is likely to outstrip supply.

Andrea Kruse ’08, who works for the US Forest Service, says, “We’re desperate for archaeologists—I don’t think we’ve had this many projects since the thirties.” She attributes part of the influx to the Great American Outdoors Act, which passed in 2020. It provides funding to repair and upgrade infrastructure and facilities on federal land. As a lot of deferred maintenance starts up again, Kruse and others like her are being called in to assess relevant areas for cultural and historical significance.

Most federally funded and many private development projects require a preliminary archaeological survey. For example, if a company is leasing public land to establish a bentonite clay mine in a canyon, or a state Department of Transportation wants to widen a highway, one of the first steps is an archaeological survey. Many archaeologists do this kind of work for a federal agency or a private consulting firm.

Andrea Kruse ’08 (second from left), pictured here near the base of Mt. Adams in Washington, has worked as an archaeologist with both the US Park Service and the US Forest Service.

For such a small college, Luther has a big presence in the field, with professionals working at high levels across the country—including right here in Winneshiek County.

Hyper-Local Archaeology

Bear Creek Archeology (BCA) in Cresco, Iowa, is practically a Luther pipeline. Started in 1983 by David ’77 and Lori (Van Gerpen) Stanley ’80, Luther professor emerita of anthropology, the firm has a long tradition of hiring Luther students and graduates for its cultural resource management projects throughout the upper Midwest. (Betts also worked at BCA.)

Among its current employees is Derek Lee ’96. Lee joined BCA the year he graduated. Since then, he’s seen dozens of Luther grads get their start at the firm.

Lee’s carved out a niche for himself at BCA in custom software design. “Archaeology is not like, say, health care where there are companies upon companies that develop software specifically for that industry. We tend to take from other sciences and adapt,” he explains.

Ground-penetrating radar and GIS have been adapted to archaeology quite readily, and Lee has designed databases to better serve BCA projects and analysis. He and his team also use an organizational system that allows them to easily compare maps and surveys across decades and even centuries. “A lot of what we do can be figured out here, in- office, so that you’re really well prepared and limit surprises when you get out in the field,” he says.

As an archaeologist at a private consulting firm, Shay Gooder ’08 splits his time between evaluating sites across the Midwest and back at the office in Cresco, Iowa, analyzing artifacts and writing reports.

Another BCA employee is Shay Gooder ’08. He grew up in Cresco and wasn’t planning to attend college so close to home, but Luther’s anthropology department, he says, “won me over big time. I just wanted to learn under them, and I have zero regrets. Colin Betts is one of the best in the nation, and I’m very fortunate I got to work with him—I don’t think I could have been better prepared.”

Gooder has a particular interest in geomorphology (the relief features of the earth) and soil processes of the Midwest. When BCA is asked to evaluate a project site, Gooder is one of the people who goes in to assess. “The soil stratigraphy is telling us how things have developed in that area over the last 15,000 or 20,000 years and the probability of having a prehistoric or historic site on it,” he says.

BCA completes projects across Iowa, Minnesota, Illinois, Missouri, even into Nebraska and South Dakota. One that Gooder especially remembers was in Iowa, when excavation revealed a series of thin black lines in the soil. When these lines were mapped out, they showed a number of geoglyphs (large-scale drawings on the ground) that suggested people built and rebuilt the outlines. “It might sound mundane talking about black lines in the soil,” Gooder says, “but from an archaeological perspective, I was really excited to be a part of it. Getting as much data as we can regarding these areas that were utilized over thousands of years warrants protection and analysis. When they’re gone, they’re gone forever.”

A Balancing Act at the Federal Level

Often, practicing archaeology means balancing development and preservation. Marit Bovee ’04, who works for the Bureau of Reclamation, experienced this dynamic in her former work with the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM). “Every agency has its mission,” she says. “The BLM’s mission is multiple use, so they’re balancing the needs of recreationalists against the needs of oil and gas operators who have a permit to drill a well for oil extraction. As an archaeologist, you’re always trying to find that balance. You’re always trying to make sure that you’re following the process in the law so resources can get identified and evaluated for the National Register of Historic Places. We always shoot for avoidance of impact to archaeological sites, but if it isn’t possible, we start mitigation.”

When working with the Bureau for Land Management, Marit Bovee '04 installed interpretative panels at the Big Cedar Ridge Fossil Site in the Big Horn Basin of Wyoming.

Mitigation involves onsite data recovery, public outreach to make sure people know what’s happening, and possibly securing public interpretation materials or documentation. Developing those mitigation measures occurs in partnership with state historic preservation offices. There’s one in every state, and all projects need to go through them.

“The other major partners are the affected tribes,” Bovee says. “Tribal consultation is a constant dialogue to make sure the tribes are aware of what’s happening, that their concerns are heard, and mitigation includes a benefit to the tribal community in some way. Finding that balance is pretty much a daily task.”

Andrea Kruse ’08 says that her training as an anthropologist helps her to find solutions to these difficult questions of balance. Kruse, who grew up on a farm in Nebraska, has worked for both the US Park Service and the US Forest Service. She’s currently an archaeologist at the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington state.

When the US Forest Service is preparing to sell timber rights, Kruse and her colleagues first examine whether there are critical cultural resources that need to be protected. She draws on her troubleshooting skills constantly. “Sometimes we’re really seen as the big bad wolf,” she says. “You say archaeologist and people freak out. But it really comes down to, how can I help do something without destroying A, B, C, or D?

“It’s really trying to use that problem-solving and framing things in a way that people understand why something needs protection, why it’s important for other cultures or other people. It really goes back to working with multiple groups and using that anthropology knowledge of sitting back, listening, and then trying to propose a solution.”

Historic Preservation

Branden Scott ’04 is a Bear Creek Archeology alum. After a decade there, he moved to Des Moines and made a pitch to Impact7G, an environmental services firm, to start a cultural resource management division, which he ran for several years. “It was a mix of doing field work and business,” he says, “which is why an education like Luther’s is important. I took accounting and a very diverse range of liberal arts at Luther, which helped me later transition between those two worlds of scholarly archaeology and business.”

Branden Scott ’04 (second from left) earned a 2022 Excellence in Archaeology and Historic Preservation Award for his 1,700-page study of low-head dams in Iowa. He recently took a position at the Iowa State Historic Preservation Office.

Scott’s work during his time at Impact7G earned him a 2022 Excellence in Archaeology and Historic Preservation Award, bestowed by the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs. His two-year project on behalf of the Iowa DNR investigated low-head dams in Iowa—over 130—to determine which would be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The 1,700-page report is now a working document for the DNR and federal agencies as they decide how to move forward with their various dam projects.

That study involved sometimes grueling site visits as well as working with historical societies across the state, digging through thousands of newspaper articles from the period to understand why and how the dams were constructed. The study also involved major collaboration between two state agencies, two federal agencies, and five Impact7G departments. “There are so many aspects of archaeology that I don’t think are obvious to the layperson,” Scott says. “The liberal arts education really comes into clear view when you talk about this. We’re pulling in a lot of different skill sets and different resources to do this work.”

Scott’s award-winning report has become a reference point for federal agencies as they decide how to move forward with various projects related to low-head dams like this one.

When an opportunity arose to join the Iowa State Historic Preservation Office, Scott jumped at the chance to take a bird’s-eye view of these kinds of projects. Now he reviews projects for compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act.

“People have ties to place, and they have ties to history,” he says. “All of these places and stories and events help frame who we are in the now and create our sense of community and identity. So preserving parts of our past also preserves part of who we are, part of who our kids are going to be. That’s important.”

Restorative Justice in Archaeology

As a field, archaeology has a problematic past. Studies have often sidelined indigenous knowledge in favor of racist, colonial interpretations. Frequently, Western, mostly white institutions have established digs and appropriated artifacts from colonized places. But despite its past harms, there’s plenty of opportunity for the field to course-correct.

Kari (Sandness) Bruwelheide ’89 has worked at the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History for 31 years. When she attended grad school at the University of Nebraska, she volunteered for a repatriation project that involved returning human remains in the university’s museum collection to tribes. “That opened up doors I never imagined I would have walked through,” she says. “That was really pivotal in changing my focus.”

Bruwelheide became fascinated by the stories that bones tell. “There’s no stronger piece of evidence that can tell you more about a person,” she says. “Human remains are like a book. They record the biological aspects of our identity—our age, biological sex, ancestry. They provide information on our diet, our health, our activity patterns in life, disease, and other cultural markers that we don’t think about.”

In combination with where a person was found and how they were buried, she says, “It’s a very intimate way to look into history, into the past.”

Kari (Sandness) Bruwelheide ’89, a biological/forensic anthropologist at the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History, excavates a site in Virginia.

As a biological/forensic anthropologist, Bruwelheide gets called in when human remains are suspected or uncovered at a site. She was recently featured in the Washington Post for her work on the grave of a teenage boy who was likely one of the first European settlers in Maryland, possibly in the 1630s. She also works with law enforcement on forensic cases.

Currently, Bruwelheide is at work on a project involving an African American cemetery in Catoctin Furnace, Md., that was disturbed by road construction in the 1970s. At the time, portions of the unmarked cemetery had to be removed. The human remains were taken to the Smithsonian, where they were identified as people of African ancestry. Contemporary residents of the village don’t have obvious African ancestry, and the community’s history was almost entirely centered on the European immigrants who worked the iron forge until it closed in 1903.

In 2015, Bruwelheide says, “We were contacted by the historical society of that small community. They wanted to incorporate the experiences and contributions of African Americans into the early history of their community, and begin to repair and restore what time and slavery had destroyed. So they asked us to do more investigation on the people who’d been buried there and find out as much as we could about them.”

Bruwelheide’s team worked with a nearby African American community in Frederick, Md., to ask what questions they wanted answered. First and foremost, they wanted the descendant community found. And so the Smithsonian, working with geneticists, has identified familial relationships within the cemetery and ancestral origins in Africa, and they’re starting to identify living descendants of these people. “It really shows how our field can also be reparative and a tool for social justice in ways that I never would have imagined,” Bruwelheide says.

The investigations have uncovered that the people buried in Catoctin Furnace were ironworkers—probably enslaved ironworkers—who lived between 1776 and 1840, when the owner of the ironworks transitioned from enslaved labor to European immigrant labor, and the African American community there disappeared.

“Their history and contributions toward establishing industrial America have been lost and their family ties severed,” Bruwelheide says. “Slavery was not just on plantations. These skilled ironworkers helped build industrial America with knowledge brought from Africa. We’re trying to restore their story and give their descendants the ability to reconnect with their ancestors.”

She continues, “Our field is dealing with a racist and colonial past—it’s really a reckoning within our field. And we’re looking at ways to do no further harm and to work toward restorative justice. It’s going to take a lot of work. The communities that have been the victims of that past have a lot of distrust. Going forward, we need not only to do the work, but also to repair the relationship with the living communities that exist today.”

She says, “It’s a complex field—I’m not going to lie about that. But I feel really strongly that biological anthropology can be a positive force of restoring history, restoring knowledge, and that it can be used for reparations today, even when in the past it was used for just the opposite.”

Archaeology Today

With the need for cultural resource management workers higher than ever, Luther’s anthropology program is considering curriculum revisions to provide students with a more clearly articulated path to this career. Betts says that the program also wants to make field school more accessible to all students by integrating it into a normal semester rather than during the summer, when extra room and board costs and lost summer employment wages can be prohibitive.

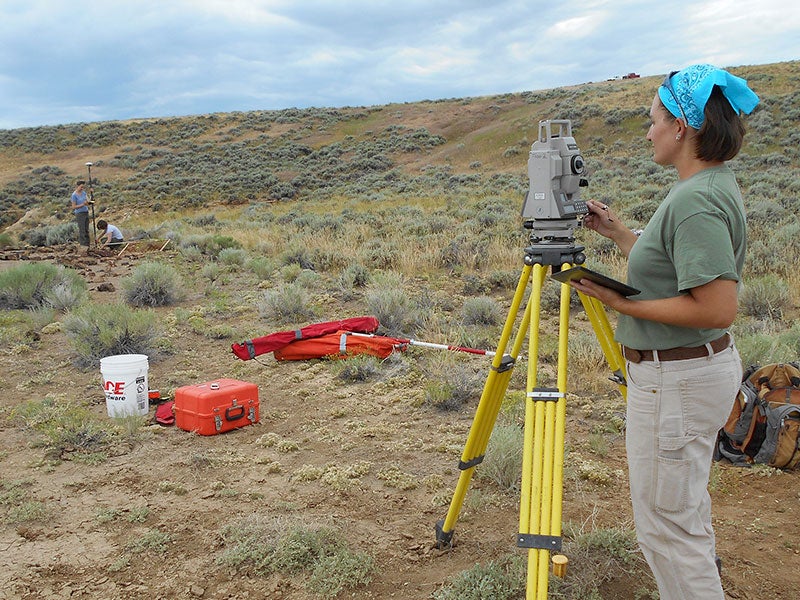

Professor of anthropology Colin Betts '93 (far left) teaches ground surveying techniques to students during Luther's archaeological field school.

This would be a service to Luther students and also to the discipline. Making archaeology accessible to people of all backgrounds would go a long way in a complex field that’s actively reckoning with its injurious past. And it would go a long way toward helping to grow human knowledge, understanding, and connection.

“Good knowledge of the past allows us to better comprehend where we are in the present, I really believe that,” Bruwelheide says. “The more we can learn and understand the truth of history and the experiences of a diverse number of people, the better we become at dealing with the situations we face today. Archaeology is a powerful tool to bring us together in the present.”