Anthropology Lab and Collections

The Luther College Anthropology Program manages three collections of material culture: Ethnographic, Archaeological, and Numismatic Collections.

The ethnographic collections consist of over 1,000 objects collected from around the world. Our archaeological collections, primarily focused on the prehistoric and historic peoples of Northeast Iowa, details over 8,000 years of human history in the Upper Midwest. Finally, the numismatic collection consists of an assortment of coins and notes from around the globe. Luther’s collections contain a wealth of cultural and historical information that can be used in numerous ways to educate as well as fascinate those who would otherwise not have a chance to experience and appreciate such diverse cultures.

The anthropology collections are supported in part by an endowed fund established for the purpose of managing and maintaining a material culture resource in perpetuity. The management and preservation of our collections is intended to provide the Luther College faculty, students, and outside professionals with a useful resource for scholarly research. The collections are also made available to surrounding communities to be used in outreach programs, exhibits, and other educational forums to facilitate appreciation and understanding of Iowa’s and the world’s rich heritage. The collections are administered by faculty member and director Colin Betts and managed by the laboratory and collections manager Destiny Crider.

Resources for Luther’s Anthropology Lab include:

- Computer workstations with ArcView, SPSS, Microsoft Office, and other software

- Digital cameras, GPS and Total Station equipment

- NextEngine portable 3D scanner

- Transcription machines, stereoscopes, GPS and Total Station equipment

- Teaching collections which include a wide range of prehistoric stone tools, ceramics, faunal material, raw stone collections, and an osteology collection

- Former Professor R. Clark Mallam’s slide collection containing historic photographs, teaching illustrations, excavation photos and aerial photographs of outlined Effigy Mounds

The anthropology lab offers a number of work-study positions to students with interests in anthropology, history, and museum studies. The majority of the work our students do is related to the documentation and preservation of our archaeological and ethnographic collections. The primary activity in the anthropology lab is cataloging and inventorying our collections, which involves training in cataloging and basic analysis techniques, digitization of records, and digital photography and data entry of collections information.

Students may also be given the opportunity to work on exhibits or online projects such as collections galleries, as well as conduct collections research, assist with research requests and loans, and assist with community education and outreach programs.

The range of activities encompassed by work study in the anthropology lab provide students with valuable experiences that are directly applicable to future careers in the field.

As the Anthropology Lab exists to support the program and its majors, anthropology majors are given preferential consideration when assigning positions to applicants. Under certain circumstances the Anthropology Lab will employ non-majors or individuals with academic interests outside of the field when skills, knowledge, or resources dictate.

To apply for a work study position, complete the Work Study Personal Information Sheet and return to the Anthropology Lab (Koren 319) or send an email with completed form to Destiny Crider.

In some ways, I began my museum career during that first shift in the lab. When I interviewed for my master’s degree program, the professor was floored that I basically had four years of museum experience under my belt.

Megan Clark '05

Archaeological Collections

Explore our Archaeology Collections – A newly developed online searchable database supported in part by the State Historical Society of Iowa Historical Resource Development Program.

The archaeological collections contain well over 500,000 prehistoric and historic artifacts. First started in 1969 with the acquisition of the Gavin Sampson Collection, the archaeological collections have been augmented over the last 40 years through donation and field research. While the collections represent the full range of human occupation in Iowa, Oneota and Woodland Tradition (500 BC to 1700 AD) materials are the most prevalent.

Shell Effigy Fishing Lure

Acquired Private Collections (approximately 37,000 artifacts)

- Gavin Sampson Collection—collected from over 130 sites in Northeast Iowa and hundreds of locations across the Midwest

- Henry P. Field Collection—collected from various locations in Allamakee County, Iowa as well as purchased or traded materials from across the United States

- Robert Stoddard Collection—collected from sites in Allamakee County, IA and western Wisconsin

Field Research and Contract Excavation Collections (over 500,000 artifacts)

- Excavations at Cerro Gordo, Panama

- Contract excavations conducted for various agencies and businesses across Iowa

- Field School and research excavations

A Woodland style ceramic pot rim sherd

The Gavin Sampson Collection

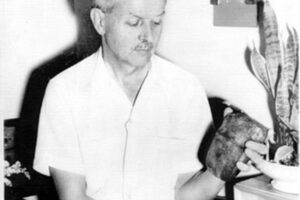

Gavin Sampson poses with some of his artifacts

Gavin Sampson was born May 8, 1922, 12 miles northeast of Decorah. He lived his whole life in the Decorah area with his wife Dorothy Sampson. Sampson found his first artifact in 1930 at the age of 8 when he discovered an arrowhead in his backyard. He quickly ran indoors to show his parents his amazing discovery. This find marked the beginning of a lifetime of collecting, during which Gavin Sampson contributed greatly to our understanding of Iowa’s prehistory. He often spent his free time exploring the past, spending weekends outdoors walking fields and adding artifacts to his collection. He loved to read material about archaeology and America’s first inhabitants.

After serving in the Army in World War II, Sampson returned to Decorah where he worked as a project inspector with the Iowa Department of Transportation for 25 years. His job with the Department of Transportation gave him ample opportunities to investigate prehistoric peoples in Iowa. Sampson developed a reputation for being the man to contact when artifacts were discovered during road and other construction projects. If artifacts were discovered, the workers often called in Sampson to inspect, record, and sometimes collect the artifacts.

In 1969, Dr. Clark Mallam, professor at Luther College, approached Gavin Sampson to discuss donating his collection to Luther College. Both Gavin and Mrs. Sampson wanted the collection to be on public display and felt that the collection belonged in Northeast Iowa. In 1969, the collection passed from Mr. Sampson to the Luther College Archaeological Research Center and became the foundation of the college’s archaeological collection.

The collection includes over 15,000 artifacts collected from 151 sites in Winneshiek and Allamakee counties. Sampson kept meticulous notes for many of his finds. Although many of his discoveries were surface finds he also did some excavating on private land. In many cases he was the first to identify and describe the location of sites, especially in Winneshiek County. He often drew a map of the site location, recording his impressions of the site and whether the site had been disturbed or collected before. Each site he discovered was recorded using the trinomial system, the same method used by most archaeologists in the United States. Each artifact was then recorded and labeled to identify which site it was collected from. When the Smithsonian’s George Metcalf helped Luther organize and catalog the collection in 1970, he praised Sampson’s “professional quality” record keeping.

Sampson’s collection represents over 12,000 years of Northeast Iowa’s past. Chipped stone tools and pottery fragments comprise well over half of the total number of objects in the collection. Other notable artifacts from the collection include Catlinite objects, historic and prehistoric pipe fragments, celts, axes, atlatl weights, and gaming pieces. The overwhelming majority of artifacts from the Sampson Collection are culturally associated with the Oneota Tradition, dating between AD 1350 and 1700. Associated with Siouan-speaking peoples, the Oneota tradition is believed to represent the ancestors of the modern Ioway, Oto, Missouria, and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) tribes.

The Gavin Sampson Collection provides the faculty and students at Luther College an invaluable resource for conducting research. Over a dozen students have utilized Sampson’s collections while conducting original research. Additionally, his maps and notes have provided a priceless means of identifying archaeological sites suitable for teaching students excavation methods. To date, Luther College has excavated seven sites recorded by Gavin Sampson and represented in his collection. His collection is also used as a resource in many Archaeology classes and community programs. It continues to inspire, inform, and generate research, as well as providing residents of Decorah and surrounding communities the opportunity to learn more about the original inhabitants of our state.

The majority of information on this page can be found in an article written by Neil Mick and Jennifer Putzier titled “Profiles in Iowa Archaeology” Journal of the Iowa Archaeological Society 48 (2001).

For more images of Gavin Sampson’s Collection, visit our full Flickr set. You can also explore the entire Gavin Sampson collection through our online artifact catalog.

The H.P. Field Collection

Henry P. Field holds one of the many axes in his collection.

Dr. Henry P. Field was born in 1902. He graduated from the University of Iowa Dental College in 1926 and then moved to New Albin, Iowa to practice. While in New Albin, Field met Ellison Orr, a civil engineer with extensive experience in archaeological excavation and recording techniques. They began going on outings to collect artifacts while Orr taught Field more about Iowa archaeology. In 1930, Field moved to Decorah, Iowa to start his own dentistry practice. He maintained contact with Orr and they continued their outings together with Clifford Chase, Charles Keyes (a noted archaeologist in the state of Iowa), and Dale Henning, a Luther faculty member (at the time). Henry Field was also active in the creation of the Iowa Archaeology Society and Effigy Mounds National Monument.

Along with his colleagues, Field covered quite a large and varied area on his outings. He concentrated on Winneshiek and Allamakee Counties, but he also traded and purchased artifacts from numerous locales outside of Iowa. He would usually go out for the day with his colleagues and spend the whole day collecting artifacts from the surface. The route they took varied based on road conditions and weather, but generally followed Bear Creek or the Upper Iowa River, west from Decorah, with stops in Waukon and New Albin and then back to Decorah. This circle was known to Field and his friends as the “Indian Circle” and it included most of Dr. Field’s favorite sites like the New Galena Mound Group, Flatiron Terrace, and Sand Cove.

H.P. Field donated parts of his collection to Luther College in 1969 and 1970. The rest of his collection was split between Effigy Mounds National Monument and the Office of the State Archaeologist at the University of Iowa. Field collected many different types of objects including numerous shell objects, glass beads, metal ornaments, chipped stone and bone tools, and ceramics (which were used as tools or decorations). Field also collected a number of geological specimens which are now housed in the Luther College Geology Collection. The portion of H.P. Field’s collection in the Luther College Archaeological Collection consists primarily of artifacts which lack provenience information.

Historical Archaeology Collection

Although the majority of the archaeological collection housed at Luther consists of prehistoric Native American artifacts, the college also possesses historical artifacts from several sites across Iowa. These sites include Terrace Hill in Des Moines and the Seth Richards site in southeastern Iowa.

Historical archaeology in North America begins with European contact, spanning from the first written accounts of European explorers and continuing on into the early 20th century. It is unique from prehistoric archaeology in that there are additional forms of evidence, most often written or printed materials, available to researchers. These can include diaries, court documents, or perhaps even first-hand accounts by people who experienced the history of a site. Such documents can assist archaeologists in locating sites, understanding what artifacts they have excavated, and give them clearer pictures of who lived on or utilized a site. These records may corroborate data recovered at a site or it could potentially contradict the archeological record, forcing archaeologists to reevaluate both forms of evidence. Like prehistoric archaeology, historical archaeological sites have a wide range of variation ranging from humble frontier houses to large Victorian mansions, from early industrial sites to shipwrecks.

The artifacts found at the sites also display a wide range of variation. Some of the most common artifacts from European inhabitation are historic ceramics and glass. Although both of these objects are relatively fragile, they remain in the ground for centuries without decomposing like bone or wood. They are also incredibly helpful due to their stylistic and technological changes over the years, allowing historical archaeologists to date sites based on the type of ceramic or glass excavated.

If a particular site exists within the historic period but lacks associated historical documents and accounts, historic ceramics are one of the primary methods of dating a historical site. Because styles and technology change over time, the type of ceramics found can often be used to narrow down the time frame of a site to a few decades. Ceramics have also been used as a means to reveal the socioeconomic status of a site’s inhabitants. As might be expected, finer and more expensive wares, such as delicate ceramics imported from China, are usually a sign of greater wealth. Rougher and cheaper ceramics, such as those produced in a home or in mass quantities, might indicate lower economic status. By identifying specific ceramic wares, archaeologists can then use historical documents—such as catalogs and store ledgers—to indicate or corroborate evidence of social status or function at a particular site.

Ceramics are often identified based on three primary attributes. The first of these is the paste, which is the characteristics of the raw material used to make the ceramic. Another attribute is the surface treatment, which involves the manner in which the vessel is covered or glazed. The last is the decoration, which is interesting in the way the piece is decorated with various patterns, motifs, color scheme, and even method of decoration. These three factors define each unique type of historic ceramic, allowing for easy identification and dating. Analysis of historic ceramics is aided by accounts and descriptions of the various wares written by the manufacturers or by contemporary people interested in the art of ceramic making.

The Florida Museum of Natural History has created a digital type collection containing ceramics from Europe, America, and Asia. The site is useful for both learning more about historic ceramics and for identifying the various types.

In addition to historic ceramics, glass is often found at historic sites. This is most often fragments of glass bottles or window glass. Bottle glass, like ceramics, can illuminate much about a site. By using various physical and manufacturing features, such as shape, color, and seam characteristics, a glass bottle can often be dated to a specific decade. This is because manufacturing techniques for bottles were always changing as new technology became available, proving helpful for archaeologists attempting to piece together the past.

Bottle type is also useful for understanding the function of a site. These types include unique bottle styles for liquor, champagne, beer, medicine, canning, and soda water just to name a few. Bottle types are identified by a label found on the bottle (rare) and its shape, color, or method of manufacture. For example, champagne bottles are often round in cross-section, and are often made from an olive green, olive amber, or colorless glass. In contrast, soda bottles were made from relatively thick glass, round in cross-section, and made from aqua or clear glass. Some bottle types, such as medicine bottles, run the gambit of shapes, colors, sizes, and manufacturing methods, and are therefore more difficult to identify without additional context.

You can learn more about historic glass bottles as well as identify any in your possession on the Society for Historical Archaeology website.

The Governor’s Mansion: Terrace Hill

Perhaps the most well-known historical site excavated by the Luther College Archaeological Research Center is the gardens at Terrace Hill, a 19th century mansion which now serves as the residence of Iowa’s governors. Constructed between 1866 and 1869 by Iowa businessman B. F. Allen, the palatial residence was an imposing site on the landscape of early Des Moines, standing almost 90 feet high and constructed with 15-foot ceilings, twelve-foot arched doorways, and custom made furniture, mirrors, carpets, statues, and more.

As B.F. Allen’s fortune waned in the last quarter of the 19th century, he no longer had the funds to hold onto his “Prairie Palace”, and sold it to fellow businessman Frederick M. Hubbell. After Hubbell’s death in 1930, Terrace Hill was held in trust by his family. In 1957, none of the Hubbell heirs wished to live at Terrace Hill, and for 15 years the house stood empty. As the Hubbells sought to find an occupant for their home, it became clear that the only suitable owner of the property was the state of Iowa. Coupled with the fact that Iowa’s national and international profile was rising and the then governor’s residence was becoming inadequate, the state of Iowa accepted the donation of Terrace Hill from the Hubbell trust. As the state gained ownership, questions started to rise as to what improvements should be made to the house. Should it be modernized or restored to its original look? Should the governor live in the entire house, or should part be turned into a museum? It was eventually decided that the third floor be converted into a residence for the governor, the second floor into a conference and office area, while the first floor and the grounds should be restored to their original state.

It was towards the goal of restoration that Luther College was called in to excavate at Terrace Hill. In 1981, under the direction of Dale Henning, a group of Luther students dug on the grounds of Terrace Hill in order to ascertain the exact location and dimensions of the 19th-century garden. Their secondary goals included determining the age and location of the greenhouse known to have existed, as well as identifying any other features present in the garden. Through both excavations and soil probing, they were able to locate the greenhouse and the shape of the garden, as well as identify a few independent structures, one of which may have housed a boiler to heat the greenhouse. Artifacts collected at the site include large panes of glass, verifying the presence and location of the greenhouse, and a few pieces of fine garden art, relaying the wealth of the site. Having succeeded with their stated goals, the excavations of Luther College students allowed the garden to be reconstructed and restored to reflect how the garden appeared in the 1860’s.

More information about the history of Terrace Hill can be found in the Winter 1979 issue of The Iowan, or by visiting the Terrace Hill website.

The Seth Richards House: Bentonsport’s First Postmaster

During the construction of a new bridge spanning the Des Moines River near Bentonsport in Van Buren county, archaeologists noticed that the proposed new roadway corridor would pass through a lot where a historical house had been mapped in the late 19th century. According to historical accounts, the site had burned down sometime around 1915. Archaeologists then set out to excavate bits of the site to see what remained of the house’s foundation and to carry out archival research to yield information regarding the house and its occupants’ relations to historic Bentonsport. This investigation uncovered that the house in question belonged to Seth Richards, the first postmaster of Bentonsport and regional entrepreneur who had served from 1838 until 1847. Richards had most likely built his house sometime between 1852 and 1866, according to historical accounts.

Archaeological investigations began in the summer of 1983. Knowing that the site would eventually be covered by the new roadway, archaeologists worked diligently to learn as much about the site as possible before construction. In addition to documenting structural features and artifact patterns, archaeologists sought to use the data to understand living conditions and lifestyles of various social groups in 19th-century Iowa. Having excavated a small house the previous summer across the Des Moines River in Vernon, Luther archaeologists could compare the living conditions of the residents of that site with the more economically well-off residents of the Seth Richards site. Vectors for comparison included dishes, tools, personal effects, architectural hardware, and food.

The nature of historical archaeology shines clear at the Seth Richards site. Utilizing documents unique to historical archaeology, the excavations were also assisted by first-hand accounts of the house by Ms. Grace Kemp. Ms. Kemp, who lived in the house from 1908 until 1913, revealed many details about the house’s configuration. It had a large front door with panels of side lights, a two-story frame with gable end façade, and brick fireplaces in several rooms. She also could remember the number of rooms in the house and gave archaeologists a rough idea of where each one was located, their use, and what sorts of materials were used in their construction. Her description of the residence was corroborated by a postcard from c. 1910. Ms. Kemp also confirmed what archaeologists had gathered from other sources that the house burned down in 1915.

Ethnographic Collections

Explore our Ethnographic Collections – A newly developed online searchable database supported in part by the State Historical Society of Iowa Historical Resource Development Program.

The Ethnographic Collection comprises over 1,000 objects, representing people and cultures from around the world. The collection has grown over the last one hundred years by the donation of objects collected by Luther alumni and faculty, as well as family and friends of the college and Decorah area residents. Objects in the collection represent every continent on the globe with the exception of Antarctica. Some countries represented in our collections include: China, France, Holland, Japan, Turkey, Norway, Nepal, Madagascar, Peru, and Australia.

The largest portions of our Ethnographic Collections were compiled by two individuals who performed missionary work among indigenous people in Alaska and South Africa, Reverend Tollef Brevig and Hanna Astrup Larsen, respectively. Their stories illustrate the rich history associated with our collections.

The Reverend Tollef L. Brevig Collection of Inupiaq Material Culture

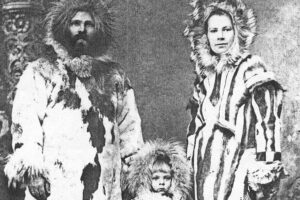

The Brevig Family Courtesy of the Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum.

Rev. Tollef Larson Brevig worked as a missionary and teacher to the Inupiaq (or Inuit) people in the area of Teller, Alaska for nearly 23 years. He was born in 1857 in Norway and immigrated to America ten years later. Brevig attended Luther College from 1872 to 1876. After graduation he worked as a schoolteacher until 1891, when he was ordained as a pastor in the Lutheran Church.

In 1894, Brevig was commissioned by the U.S. government to move to Teller, Alaska, 60 miles north of Nome on the Seward Peninsula. He was to serve as minister to the Inuit, as well as a group of Norwegian Lapplanders (Saami) commissioned and relocated by the Federal Government, to teach the Inuit how to herd caribou. One condition the Saami people had was that a Lutheran minister be provided for their religious needs. Brevig, along with his wife and children, founded the Teller Mission and stayed with the Inupiaq long after the Saami had returned to Norway.

T.L. Brevig was known to the Inupiaq as Apaurak, or “father of all.” He learned to speak their language and became a member of their community where he served numerous positions including schoolteacher, doctor, postmaster, and harbormaster. He worked to improve the social welfare of the Inupiaq people and developed great respect for them. Brevig left his mission in 1917, having acquired over 100 objects representative of the everyday lives of the people he served. His collection includes skin pouches, hunting and fishing equipment, carved ivory, wooden boxes, soapstone lamps, and a variety of ritual and decorative objects. The objects pictured on this page represent only a small portion of the Brevig Collection.

View the Alaska objects in our online object catalog.

The Hanna Astrup Larsen Collection of Zulu Material Culture

Hanna Astrup Larsen was born in 1873 as the daughter of Ingeborg Astrup and Laur Larsen, Luther College’s first president. She grew up in Decorah, Iowa and was home schooled by her mother. Through Norwegian American connections, Hanna was given the opportunity in January 1897, at the age of 24, to join her sister Marie in South Africa at a Zulu Mission Station while accompanied by her uncle and aunt. During her three years in Zululand on the Entumeni Mission, Hanna was able to gain a first hand knowledge of Zulu culture as well as a collection of objects that were later donated to Luther College. Once back in Decorah in the spring of 1900, Hanna was able to look at the world with a new cultural perspective.

Ethnographic Collection

Items donated by Hanna Astrup Larsen were given to the collection on 22 October, 1900. There are a total of 77 objects that are part of the Zulu collection from Natal, South Africa.

View the collection of Zulu materials through the online catalog.

Literature

Hanna Larsen described Zulu life and culture in her book, Skisser Fra Zululand, published in Norwegian in 1905 and then translated into English as Sketches from Zululand, in 1994. By taking on a woman’s perspective, Hanna wrote about and collected objects that related to domestic life, particularly ones representing everyday events. Instead of focusing on weapons or objects of strange fascination, Hanna was captivated by those that had everyday significance and that represented the Zulu culture. She had the mind of a Cultural Anthropologist and an Ethnographer.

History

The Bethany Indian Mission, which began in 1884 as a small school in Wittenberg, Wisconsin, was established by Norwegian missionaries as a way to bring the word of God to the Indians living nearby. The buildings that would make up the mission were built under the direction of a committee from the Norwegian Synod. While later pastors would imply that the mission was set up as a way to give back to the Indians for the “gift” of the land that settlers now occupied, its original purpose was to convert Indians to Christianity and to change their lifestyle to resemble that of the settlers around them.

There was some legitimate sympathy behind the mission for the difficult living conditions of the Indians who lived nearby, but this sympathy conveniently ignored the fact that such poor living conditions were caused because settlers had taken possession of the most resource-rich land and left the Indians with whatever was left. This sympathy was also tinged with the feeling that the Indians’ way of life was misguided and wrong and that indoctrinating them in Christianity was for the best.

This view comes through quite clearly in one of the letters that Pastor Brynjolf Hovde wrote in 1893, when he was newly installed: “My family would not have to sit at the same dinner table as the Indian children, would they?” Such a sentiment reveals the true feelings that were felt about the students at the Mission.

Luther College’s connections to the Mission were primarily through Rev. Ernest W. Sihler and Professor Axel Jacobson, both of whom had attended Luther before being employed by the Mission.

The number of students attending the school increased over the years from about eight or so in the first few years to over 150 children by 1894. By the time the school closed down in the 1930s the number had steadily dropped.

Collection

Rev. Ernest W. Sihler donated the majority of the items in the collection, with some coming from Professor Axel Jacobson as well. Both Reverend Sihler and Professor Jacobson acted as superintendent of the Bethany Indian Mission, with Professor Jacobson from 1893 to the 1920s and Reverend Sihler from 1935 to 1955. Items in the collection include baskets, doilies, and drawings. The whole collection can also be viewed to see everything else. Many of these items were made at the Bethany Indian Mission, while others were traditional work gifted to Rev. Sihler and Professor Jacobson. Several of the photos of the mission itself and activities associated with it can be viewed as well.

Numismatic Collections

Explore our Numismatic Collections – A newly developed online searchable database supported in part by the State Historical Society of Iowa Historical Resource Development Program.

In addition to extensive archaeological and ethnographic collections, Luther College also possesses a substantial collection of historical currency and commemorative tokens, which is referred to as the Anthropology Lab Numismatics Collection.

The study of coins, called numismatics, has had a great impact on historical studies. Researching the distinctive features of coins such as inscriptions, metal composition, and depicted images are excellent ways of learning more about a particular culture. The origin of the word numismatics comes from the Greek word numos, which means “current coin.”

We are currently conducting a detailed inventory and updated catalog of over 600 historic coins, currency, and tokens that date from the 1600s to early 1900s. Much of this collection was donated to the Luther College Museum between 1890-1930. These objects are available for viewing by appointment. Check out a couple numismatic pieces featured on our online exhibit To the Cage and Back.

Liberty in History Second Floor

By Meta Miller, museum studies minor (’21)

This exhibit draws on the Anthropology Numismatics Collection to highlight the past and current trends in depicting Lady Liberty on American currency. Check the online version of this exhibit.

Hmong Collection and History

When the Vietnam War and the unacknowledged “Secret War” in Laos ended in 1975, the U.S. withdrew from the conflict, leaving their Hmong allies to fend for themselves. The only help the U.S. gave was to provide a small number of planes for transportation out of Long Cheng, the U.S. military base in Laos. These planes were supposed to be for the high-ranking military officers, but they ended up carrying everyone they could. Those Hmong who were not able to escape on the planes were forced to find their own way out of the country. The genocide that followed led to the Hmong fleeing into refugee camps in Thailand and from there many made their way to the U.S.

From 1975 through the early 1990s, a large number of Hmong refugees would make their way to Decorah from the mountains of Laos and Vietnam. With the help of local churches through the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services as well as federal laws in the form of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act or CETA of 1973 and the Job Training Partnership Act or JTPA in 1982, the Hmong refugees acclimated to their new life in America.

The Indochinese Refugee Assistance Program Appropriation Bill of 1978, the Iowa Refugee Service Center, and the Northeast Iowa Refugee Coordination Services (NEIRCS) also provided ways to help the Hmong arriving in Winneshiek County in their transition to life in the U.S. English language classes were provided by Northeast Iowa Community College. These programs also served to help other refugees, many from southeast Asia, as well as some from Poland.

Sponsors, however, were one of the primary resources the Hmong refugees had in adapting to life in Iowa. When they had questions about society or about how they were to pay for things, the refugees could turn to sponsors and church organizations for help.

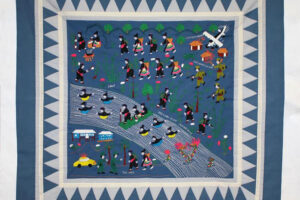

Hmong Story ClothIn order to support themselves and make a living in the refugee camps in Thailand, the Hmong made many textiles depicting their culture and experiences. This practice was carried over to the U.S. as a way to supplement their income. A sampling of these materials have been recently donated to the Luther Anthropology Collection and include story clothes and pandau, clothing, ornaments, jewelry, and dolls.

See everything in the Decorah Refugee Resettlement Collection.

Take a look at Hmong bags and their decorations or story cloths, which typically detail the journey that the Hmong took to flee and the obstacles in the way. Some also show images of cultural importance, such as the process of a marriage ceremony or scenes from folk stories. The Decorah Refugee Resettlement Collection also contains Hmong ornaments, jewelry and clothing, with intricate details and varied colors.

The Hmong textile collection is housed in permanent storage in Preus Library and is available for study by appointment in the Anthropology Lab in Koren 319. Schedule an appointment by contacting the Collections and Lab Manager (cridde01@luther.edu : Destiny Crider). Luther students and faculty are encouraged to consider the Hmong textile collection for class projects, senior paper studies, and for classroom demonstration. Destiny Crider (and Anthropology Lab Student Collection Assistants) are available to make presentations about the Hmong Refugee Resettlement Program and the Hmong textile collection. Advance planning is required in order to accommodate scheduling.

The Decorah Hmong Refugee Resettlement Program Archive is housed in the Luther Anthropology Collections and has over 10 linear feet of archival documents specific to the Resettlement program in Winneshiek County spanning the 1970s-1980s. Included are Decorah, Iowa, and nationally published newspaper and magazine articles that detail personal stories and issues relating to the Hmong refugees on their arrival in Decorah and the Midwest. The collection also houses the meeting minutes and documents of the Northeast Iowa Refugee Services organization once housed at the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church. A large collection of ESL and language training documents that were implemented with the adult English learners through the Northeast Iowa Technical Institute (Now Northeast Iowa Community College – NICC). Other papers include sponsor training materials, committee activities, and personal papers and photos of active Sponsors and Decorah community members active in different aspects of the Resettlement Program.

The Decorah Hmong Resettlement Program Archive is located in the Anthropology Lab, Koren 319. Schedule an appointment by contacting the Collections and Lab Manager, Destiny Crider.Restricted Access and Stipulations on Use In certain instances, materials may be inaccessible, or may have stipulations on use and access. Often the finding aid will tell you whether or not there are any restrictions on use or access. Some reasons why there may be limited access are:

- Copyright: A copyright holder has the right to control the use, reproduction, and distribution of those works, as well as the ability to benefit from works monetarily and otherwise. Archives must abide by these laws, which can be complex. Even if the Archives physically owns a particular document, we may not own the copyright. It’s important that you have a conversation with the staff if you want to reproduce materials, especially for commercial purposes.

- Restrictions: Restrictions come in many varieties, but they are generally legally related, classified, sensitive, or mandated by the government.

- Material condition: Sometimes, materials may simply be too fragile to be handled by researchers.

Contact Information

Britt Rhodes

Professor of Social Work

Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work Department Head

Office

Koren 318

700 College Drive

Decorah, Iowa 52101

Phone: 563-387-1623